Studies have shown that if farmers spread a quarter inch of compost on just 50 percent of California’s rangelands, 42 million metric tons of CO2e would be offset.

That’s the equivalent to all the carbon released by electricity use for commercial and residential sectors in California.

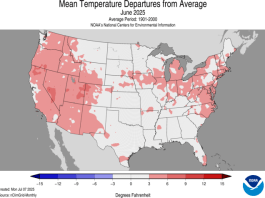

In the summer of 2022, I wrote about adapting to new climate normals and what warmer temperatures, longer droughts and more extreme weather events mean for agriculture. It was a kind of bleak picture, and I felt bad about that because I’ve tried hard to make On Pasture an uplifting place to come to in a world that can be pretty hard. So, to make up for that, here’s something you can do right now to paint a brighter future while improving your soil, growing more forage, and increasing resilience in the face of extreme weather events.

Spread compost.

I’ve been following the results of a long-running research project in California looking at what kinds of practices graziers can implement that address their needs and climate change as well. The research looked at key-line plowing, Adaptive Multi-Paddock (AMP) grazing, and applications of compost as tools for drawing carbon from the atmosphere and into the soil. The results of the different practices were compared to find which was most beneficial to graziers, and which was best at pulling CO2 from the atmosphere and sequestering it in a durable form in the soil. The project began in 2008 and measurements have been taken every year since. (You can read more on this project here.)

The results: Compost won hands down

Though the grazing treatment showed improvements in organic matter, when it came to durable carbon sequestration, the grazed-only pastures remained a carbon source, even all these years later. Likewise, the key-line plowed treatment did not show any improvements in long-term soil carbon increases. But compost showed improvements in all areas.

“When you add compost to soils, it increases plant growth, helps maintain water-holding capacity and nutrient supply, and reduces erosion,” says Dr. Whendee Silver, lead researcher on the project. “You end up with more organically rich soil and more nutrients, so the plants grow better, and those plants are pulling carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere and helping to slow climate change.”

With just one application of compost, researchers found that forage production increased by 50% in year one. When they analyzed the soil, they found they had added a metric ton of occluded carbon per hectare (2.47 acres) to the soil. (That’s durable carbon that stays put for 30 to 100 years.) The next year — with no further treatment — the soil had captured another ton of carbon, the next year another ton, and so it has continued. In fact, fourteen years later, forage production continues to be better. In addition, the soil’s water holding capacity has increased, so even through the severe California drought, forage is greener and more productive.

If you’re a grazier, those are all great reasons to spread compost, regardless of how you feel about climate change. But, if you’d like to do something about warming temperatures, extended droughts, and extreme, unpredictable weather events, spread compost. A quarter inch of compost will continue sequestering durable carbon for twenty years before you need to do another application. In fact, a 2013 study by Silver found that adding compost to just 5 percent of California’s rangelands could sequester the equivalent of 28 million tons of carbon dioxide over three years, offsetting nearly one year of emissions from the state’s agriculture and forestry sectors. Scaled up, this practice could make a significant contribution to preventing further climate change while providing plenty of food, fuel, fiber and flora.

As John Wick is fond of saying, by “carbon farming” we’re creating a system where we’re producing food, fuel, and fiber, and the more we do and the more we buy the better the climate is. It’s a win-win.

Why Compost and Not Plain Manure?

Back in 2008 when the Marin Carbon Project began this research, the first step was to get a baseline understanding of how much carbon was already sequestered in the soils in the area. As they gathered soil samples, they found that the dairy farm practice of spreading manure increase carbon dramatically–50 metric tons of carbon per hectare.

Silver says, “This sounds exciting except that cattle manure is a really big source of greenhouse gas, especially when it’s stored in piles or in slurry ponds. In fact, EPA data shows that manure management is equivalent to coal mining in terms of methane emissions. Methane is a very potent greenhouse gas, and manure greenhouse gas emissions are equivalent to mobile combustion emissions of nitrous oxide out of your tail pipes. Nitrous oxide is 300 times more potent per molecule as CO2 over 100 years.”

After additional field sampling at the dairies, and computer simulation models assessing livestock and manure emissions vs carbon sequestration, they learned that the net effect of manure spreading is high emissions.

Silver says, “That’s why we turned to compost, because composting that material actually decreases emissions.” They’ve found that if you put manure in a compost pile and turn it weekly, the result is very low methane emissions and almost undetectable nitrous oxide. Once spread on the pasture, emissions remain low.

For those wondering about compost tea as a potential solution, it just doesn’t make muster. Tests of the product showed that it was not capable of providing the same benefits and on farm trials have shown the same. For more on the reasons why, here’s a good summary.

Solving the Food Waste and Compost Supply Problems – Two Birds with One Stone

So, we know compost improves long-term carbon sequestration, but where can we get all the compost we need? Fortunately, a part of the answer to that question solves another climate problem: Food Waste. Roughly one third of food produced for human consumption is wasted and much of it ends up in landfills where it produces methane as it deteriorates. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency estimates (link here) that each year food waste creates the equivalent of 42 coal-fired power plants in greenhouse gas emissions. Solving that problem is as simple as composting food waste. Then, using that compost, we can also grow more food, fuel, and fiber while increasing carbon sequestration in the soil. It’s a win-win for us all!

But how do you get folks to compost? How do you get the compost to the farmers? Who will provide the technical and financial assistance for graziers and others implementing this practice?

We cover the answers to that here, with examples of processes and legislation you can adapt to your own region.

Moving on to Carbon Farming

While spreading compost is a good thing, it’s not the only thing. In fact, it is just one among a number of practices a farmer or grazier can implement to ensure that more carbon is going into the soil. This is called “Carbon Farming.” It is a whole farm/ranch approach to optimizing carbon capture.

If you’ve been implementing the five principles of soil health, then you’re already familiar with some carbon farming principles and practices. If you’d like to go further, you can create your own Carbon Farm Plan. To get started, check out the Planning Tools (COMET Planner and COMET Farm), developed by researchers at Colorado State University, with support from NRCS, Carbon Cycle Institute and the Marin Carbon Project. These online tools facilitate the process of developing a Carbon farm Plan and helps you estimate the potential climate benefits and benefits to your operation like greater productivity, increased soil water holding capacity and improved hydrological function, biodiversity, and climate resilience.

If you’ve been implementing the five principles of soil health, then you’re already familiar with some carbon farming principles and practices. If you’d like to go further, you can create your own Carbon Farm Plan. To get started, check out the Planning Tools (COMET Planner and COMET Farm), developed by researchers at Colorado State University, with support from NRCS, Carbon Cycle Institute and the Marin Carbon Project. These online tools facilitate the process of developing a Carbon farm Plan and helps you estimate the potential climate benefits and benefits to your operation like greater productivity, increased soil water holding capacity and improved hydrological function, biodiversity, and climate resilience.

For some more ideas of what you can do to sequester more carbon on your operation, check out the GHG and Carbon Sequestration Ranking Tool from the Natural Resources Conservation Service. They list the Practice Standard Code, the title and the beneficial attributes along with a qualitative ranking to help you choose best practices. Remember that you can get both technical and financial assistance for implementing these practices too!

For some more ideas of what you can do to sequester more carbon on your operation, check out the GHG and Carbon Sequestration Ranking Tool from the Natural Resources Conservation Service. They list the Practice Standard Code, the title and the beneficial attributes along with a qualitative ranking to help you choose best practices. Remember that you can get both technical and financial assistance for implementing these practices too!

If your head is reeling just a bit with all the new information I’ve shared here, I understand. It’s a lot. You don’t have to do all of this at once. But, if I might suggest, figuring out how to spread some compost on your pastures is a good place to start. It gets you outdoors where you can take a deep breath, you’ll grow more and better forage, and you’ll be doing something for the planet too.

And for that, I thank you!

Since I bought my first 4 cows in 1996, I have been using a winter pack bedding system to create compost the following summer for spreading on the grazing and hay ground to support the cattle. My interest in compost is partly practical and partly a carry over from growing up in a ‘Rodale’ family in PA. I’ve been making compost and spending it every year since.

Couple of observations: My experience on hay ground production gains would definitely be in the 50% range in the first year after spreading in the fall, but fall off pretty rapidly after that. Depending on availability I’ve tried to spread ~10 ton to the acre every other year, based on estimated weight of spreader loads. Spreading 1/2″ of dry compost would be maybe twice what I’ve been spreading. It would have been really great to have access to a researcher to assess the sequestration potential of the practice, but the one ‘compost expert’ from the UW that visited the farm seemed to be convinced that the process of making the compost was actually contributing more CO2 to the atmosphere than I was likely to be sequestering. That seemed off base to me, so I continued the practice. We have a small beef operation marketing perhaps 6 to 12 head per year direct.

I have a couple of questions based on your article: 1) Where did the compost come from? In the midwest, composted cow manure runs $40 per ton. You might be able to get turkey manure cheaper, but the largest producer of turkey manure in the area (Jennio) will not spread on pastures, for good reason. They feed dead cows to the turkeys and they are worried about spreading BSE. And it’s not really composted for the most part. $40 per ton, times 40 acres times 10 t/acre would be a $16,000 bill. That would not be ‘affordable’ unless you really could limit it to once every 20 years or so, which as I said, in terms of production, would not be often enough by a factor of ten.

2) Is the frequency of turning all that important? You mention ‘every week’. This is not practical on our farm, even in the driest years. We create the compost piles on the clay pack of the winter pen and turn them when we get a chance, or when it’s dry enough, or ideally when the internal temperature of the pile is below 120 or so. It’s turned with a skidsteer, as a dedicated turner is an expense that would be extravagant on a farm three times our size. The skidsteer works. In the spring, a grapple fork builds the piles quickly, the grapple is used one more time to turn the new piles, and after that the big bucket is used to turn the piles maybe twice more. By late fall, after the last grazing, or hay is taken off, but before it snows, the compost is spread on the places that need the boost most. My experience has been that a pile that is turned four times will be well enough composted to have very few clumps of unrolled hay and will largely disappear into the grass behind the spreader. On a weekly schedule I’d be looking at the tenth turning this year…. not practical, as I said.

Thanks for the article. Composting is one of my favorite things to do and think about and has been a real boon to the productivity of our grass-based farm. I’d encourage anyone with beef cattle to start composting today, particularly those who live in the north and will be feeding hay for a good part of the winter. That bedding pack that keeps your cows out of the mud in the spring, will fertilize your next years hay crop if you put in the time to make that pack into quality compost. And you probably already have the skidsteer.

Thanks for sharing your practices. I’ll answer your questions when I’m back in the office on Monday. But for now, some good news. Your compost expert now has some science that addresses their concern that composting adds more CO2 to the atmosphere than you sequester by spreading it. When I’m back in the office I’ll gather the papers that describe those results and link to them so folks can share the good news with others.

What are the materials that are composted? We unroll hay and bale graze hay. We have some hay residue but no hay waste. We have no manure waste, our cattle and horses are always ‘on pasture’ 😉. I can’t think of anything we have that could be composted.

Happy trails, Mike

Great stuff Kathy! Looking forward to learning more.

Comments are closed.