Shown here, Edmund, Normandy, Alanna and Garth and their kids. Click to visit their website and learn more about these very talented people.

For those of you who may not be familiar with the term, “bro science,” is when a dude (it’s always a dude) makes a few casual observations about a phenomenon and then launches into sweeping generalizations he proclaims loudly, widely, and authoritatively. When my brother Garth and I run experiments on our farm we generally refer to them as “cowbro science” because we’re both well aware that with our work lives centered on taking care of animals and running a marketing/distribution business we have neither the time nor attention to develop powerful hypotheses and test them rigorously. The fact that we actually are brothers and cow handlers makes it all that much better. Gently mocking ourselves helps us keep our “findings” in perspective.

With that disclaimer in place, our longest running agricultural experiment actually shows some promise. If you’re new to On Pasture or missed the article I wrote about my bamboo patch last winter you can read about it HERE.

In mid-October I completely defoliated 100 square feet of bamboo. Two years ago when I picked leaves for analysis I took leaves only and left the twigs. After watching my cows eat the plant last winter I included twigs too and left the woody cane behind because as they browsed they pulled off most of the twigs. This took the protein % down slightly (~16% instead of 18%). Total leaf+ twig material came in at 33 lbs green weight. Multiply that by 432 (the number of 100 sq ft sections in an acre) and the total wet yield for an acre of bamboo forage near the end of the growing season is 14,256 lbs, or about 7 tons. Of course we want to compare apples to apples and the only way to do that is on a dry matter basis. I sent a sample of leaves to DairyOne for analysis right after defoliating the plants and DM composed 47.5% of the weight. So… 14,256 lbs x 0.475 = 6,771.6 lbs, or a little less than 3.5 tons/acre of actual yield.

I asked my neighbor how many tons of hay he takes off the adjacent plot with identical soil. He gets about 2.5 tons/acre of high quality hay per year with a dose of NPK top-dressed in May.

Hay and standing bamboo forage are not precisely equivalent, but for my purposes they’re close enough to draw meaningful conclusions. Both will keep my animals fed through the winter. If I can get a roughly equivalent yield/acre/year I’ll be many dollars ahead. Feeding standing forage requires an order of magnitude less capital investment (fences and water vs tractors, equipment, and fuel). Strip grazing livestock requires time to set up and take down portable fences, but feeding hay does too (staging bales, cutting off the twine, giving the animals access to the bales, hauling manure if the bales are all fed in the same spot, etc). Between making hay and then feeding it out again the labor demand for strip grazing is many hours less than for an equivalent mass of hay. The hay my neighbor puts up has more feed value than bamboo leaves, so it has an advantage there, but because of all the other points in its favor I expect bamboo to save us a substantial amount of money over the long haul once I get a big enough stand going to support my cattle into the winter.

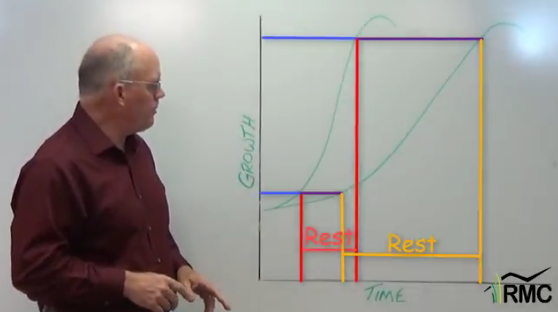

I do stockpile pasture for fall grazing, but I’ve never made it past Christmas on stockpiled pasture. I’m sure it’s possible to get into January some years in my climate (a few locals have done so), but it would be a pretty sketchy roll of the dice to count on it. The standard prescription for winter stockpiling of good quality pasture is to try to graze two or three times by the middle of August and then rest as much of the farm as possible, allowing the pasture to “stockpile” for winter. Cold weather and lack of sun shut down most plant growth by mid-October in central New York, so working back about sixty days puts us around August 15th for the start of pasture stockpiling. Describing the timing of things and making it happen in anything but a perfect year are two entirely different beasts though. Rain, temperatures through the season, number of cattle, stocking rate in pounds per acre, fertilization or lack thereof, number of grazing taken during the season, and grass/legume/forb composition are all variables at play. It can be quite a challenge to get everything to line up just right, and here is another spot I am optimistic bamboo will make for adequate winter forage. Rather than flushing suddenly in the spring and then senescing into brown straw-like feed, bamboo grows slowly and steadily all season long. It pushes new leaves from its twigs continuously through the growing season, building leaf mass in a nearly linear manner through the summer and fall. The oldest leaves pushed in June and the newest leaves from October all go into dormancy looking green and nutritious. If it works it will make for a very easy grazing plan – graze once with sheep in the spring before the new culms emerge to stunt competing grasses and then stay off the bamboo all summer and fall. Once winter hits I’ll simply strip graze the bamboo grove a single time.

I’m going to start with sheep for the spring grazing because they’re so much lighter than cattle. I run my sheep and cattle together for most of the year, but not during lambing. “Weeding” the bamboo with sheep will align nicely with a time of the year when I have the sheep flock separate anyway.The culms are quite delicate as they first emerge and I’m worried cattle hooves will snap them off below the surface if the soil is damp.

Potential yield was the final large stumbling block that could have derailed this particular cowbro experiment. Now our next step is to get bamboo growing on a full acre of ground instead of one 35 ft circle. Then I can test the sheep/cow thing and other management questions that are as yet unanswered. Stay tuned!

Want more? Visit the farm website and blog.

Found out we have a bamboo forest growing in our county in Texas. The variety they are using doesn’t spread and from what they say it has pretty good profit potential.

Hi Everybody,

Whenever Bamboo for grazing comes up I feel it is my duty to remind everyone about Kudzu, Chinese Tallow tree, and [Insert Invader Species that you hate here].

Please consider that we will all leave this planet (or our current farm) one day and what will that Bamboo do without us and our management?

Thanks.

For sure – definitely think about where it’s going to go because without management it does creep along year in and year out.

On the plus side, it doesn’t spread by seed. So it is pretty easy to contain it.

If left ungrazed, would bamboo hold it’s leaves all winter?

How was this established? Sprig planter?

How long before it’s establish would it be suitable for winter forage?

Cost/acre to establish?

Yes, it will hold it’s leaves all winter. They’re evergreen in climates just a little warmer than my location. Here on my farm the culms hold their leaves all winter, but do winterkill when it goes below about -10. In the spring the brown, dessicated leaves fall off.

It’s established by transplanting rhizomes. I haven’t tried to do it on a broadacre basis because I wasn’t sure the yield would be worth the establishment cost. And I’ve been growing up a nursery for planting out. Buying in the rhizomes is a non-starter cost-wise.

In my climate it could be grazed for winter forage the year of planting, but the yield would be very low. Year 2 would still be not so great. Only in year 3+ would the yield begin to make economic sense. I have ideas about how to transition a field into growing a bamboo winter stockpile, but that will be for future articles once I’ve actually done it successfully.

Buying in rhizomes would be $1000s/acre to establish.

Interesting! Where do you get bamboo seed in quantity?

The short answer is, you don’t. Apparently bamboo does flower every once in a long while (once every few decades). Typically it is spread by digging up a rhizome and planting it where you want a bamboo grove to grow.

How fast does the bamboo spread or does it? With a short growing season, I suspect it may not. This may be a good crop for our Texas climate, little to no snow and longer growing season. We may have a problem with deer competition here, unless it can be adequately fenced off. I like the protein levels.

It’s spreading about 6-8 ft per year right now. To get it going on a bigger patch of ground I’ll need to spread rhizomes.

That far south you could try the native cane – Aurundinaria gigantea. Canebrakes used to exist all over the place in riverbottoms in eastern North America. Cattle and hogs grazing them out though…

Years ago I had a piece of property that had what the locals call Georgia Cane. It was originally planted for erosion control. The bad thing was no matter what I used (chemical or digging it out) I couldn’t kill it. It was gradually taking over my property and I ended up selling it. Sounds like you have a way to control the bamboo, what do you use?

Interesting article. Please expand on which species of bamboo you are using, and what conditions (dry, wet, sandy, etc.) it prefers.

We’re mostly growing Phyllostachus bissetti. We also have a test plot of an unidentified Phyllostachus. I suspect this genus has the most potential in my climate, but there are others that might work under some circumstances – Sasa and Fargesia – to be specific.

I don’t know about performance on various soil types except for where I’m growing my test plot, which is a gravelly loam. I have plenty of clayey ground to test it on next, but that hasn’t happened yet.

Comments are closed.