Learning about how animals choose what to eat and where to live, and that it doesn’t work the way we thought it did, has completely changed my life. In fact, it’s why you’re reading On Pasture today. I think it can change your life too. So, over the coming months, I’ll be sharing a short course in what researchers have found, and how you can use it to grow more forage, graze more successfully, and be more profitable. Here’s Part 1.

We are so used to considering forage type, nutrition and quantity as we try to improve animal health and increase weight gain, we sometimes overlook how an animal’s interactions with it’s mother and peers affect what and how it eats. Since what a young animal learns has life-long consequences, knowing more about this process can help us be more successful managers.

A young animal learns what kind of things it should eat and do from its herd or “social group.” This explains how animals of the same species can survive in extremely different environments. For example, a calf reared in the sage-covered deserts of southern Utah and one raised on grass in the bayous of Lousiana have completely different diets and habits. This same flexibility occurs for humans as psychologist Paul Rozin points out:

“Consider the massive differences between the almost purely carnivorous diet of Eskimos and the plant-dominated diets of many tropical cultures, or between the elaborate cuisines of India or France and the relatively limited amounts of food processing carried out by some hunter-gatherers.”

Mother Knows Best

Mom has the greatest influence on an animal’s food and habitat preferences. After all, she’s been successful enough at foraging to grow up and reproduce. For young herbivores paying attention to mother is crucial for learning where and where not to go and what and what not to eat. Through interactions with mother, young animals learn about their surroundings, from the whereabouts of water, shade, cover, and predators, to the kinds and locations of nutritious and toxic foods.

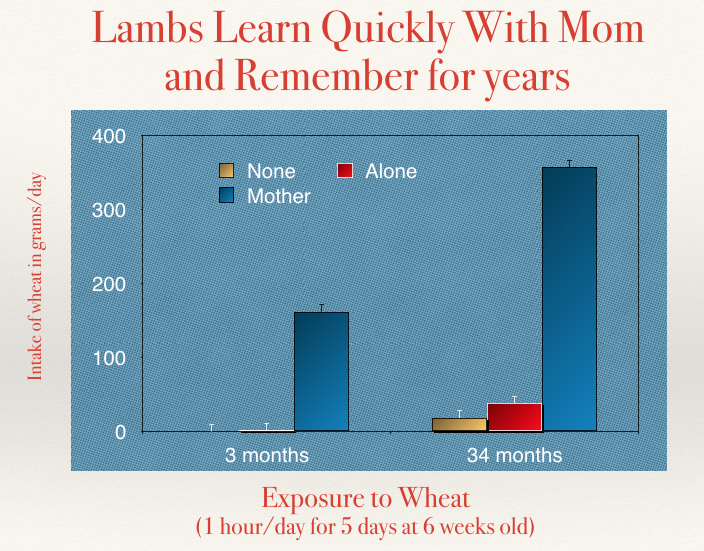

As offspring begin to forage, they learn quickly to eat foods mother eats, and they remember those foods for years. You can see the enormous importance of Mom in the graph below. In this study, the blue bar shows how much of a new food (wheat) lambs would eat. The set of bars on the left show how much lambs ate at three months, without their mothers. The lambs introduced to wheat with their mothers, shown by the blue bar, ate a lot more than the lambs without their moms. The second set of bars shows that even 3 years later, with no additional experience with wheat, the lambs who had eaten wheat with their mothers ate 10 times more than lambs who first tasted it alone.

Avoiding Toxic Foods

Research also shows that a mother can reduce her offspring’s risk of eating toxic foods. If a mother avoids harmful foods and selects nutritious alternatives, the lamb acquires preferences for foods its mother eats and avoids foods its mother avoids. You can see this in action in this video:

(There are other mechanisms at play that keep animals from poisoning themselves but we’ll cover those later.)

Learning HOW to Forage

It seems like animals should just know how to graze, right? Turns out, just like humans have to learn how to use a fork or chopsticks or how to eat corn-on-the-cob or tacos, animals have to learn different techniques for biting off the different plants they eat. This is another area where learning from Mom is important. Young animals can quickly learn by foraging with mother.

To give you an idea of the importance of experience, here’s a short video of two goats eating black brush. One is trying it for the first time. His herd mate is experienced at biting off stems and leaves.

When Does Practice Make Perfect?

When Does Practice Make Perfect?

Practice does make perfect but it really helps to start young. That’s what researchers found when they measured progress of animals as they learned to graze a new forage. The graph to the right shows bite rates nearly doubled as experience increased from no experience to 30 days of browsing blackbrush shrubs. They also found that the animals who were 6 months old learned foraging skills more readily than the 18 month old animals.

What Do You Do With This?

The most efficient method for preparing your young stock for the world they’ll live in is to have their mothers introduce them to the foods they’ll eat. So let Mom help you. If you know that your stock will be headed to a feedlot – let Mom introduce them to what they might eat there. The same goes for the forages they’ll encounter in pasture or on rangelands. Mom is a great tool for showing them how to eat poor-quality feeds you might feed in the winter or that they will find where ever they will graze.

The benefit to you of taking a little bit of time to introduce young animals to new foods is that this early experience means they are less likely to become ill and are more likely to gain weight and maintain productivity when they have this kind of experience.

After sweeping a dusting of new snow off the driveway, I went and watched our cattle pushing through a foot of recent snow. To eat the stockpiled fescue underneath.

For a 9-month calf, this was his first snowfall, so he began eating the broomstraw off the broom I’d laid down. Wish I’d taken a picture of the contrasting food choices.

Mom was showing by example: This stockpiled fescue under the snow is way better than eating the dead stems above the snow!

Comments are closed.