Dr. David Larsen’s blog, “Memoirs of a Country Vet” is one of the few that I read every time there’s a new post. I asked him to share this one with On Pasture because it’s a very important topic.

“Doc, I think I have a problem that you should look at,” Ryan said as soon as I picked up the phone.

“What’s going on, Ryan?” I asked.

“I have two dead calves out in the field this morning,” Ryan said. “Yesterday, everything was fine. The others all look like they’re doing well, but something must be going on for two calves to be dead.”

“Okay, I have some time now,” I said. “I will run by shortly and open one of the calves up. If I can’t find a cause of death, we will send you over to the diagnostic lab at Oregon State with the other calf.”

It was a short drive out to Ryan’s place. When I arrived, Ryan had the two calves pulled out of the field and stretched out in front of the pasture gate.

I looked over the grounds, and then I had Ryan pull one of the calves over to a grassy area in the corner of the barn lot.

“Just in case we have something contagious,” I said. “We don’t want to contaminate the ground the entire herd will be walk through.”

“Do you think it could be something serious?” Ryan asked.

“Two dead calves are serious,” I said. “I have seen more, and it could be something like Lepto. It is just better that I open this guy on ground that is not used by the herd.”

I pulled on a pair of gloves and grabbed a bucket of warm water and my necropsy knife.

Looking at both calves, they were in good condition and looked close to a month old. I spent a couple of minutes looking at the rest of the herd in the pasture. All the calves looked up and about. I turned my attention to the dead calf stretched out on the grass.

With the calf lying on his right side, I opened the calf’s skin along the ventral midline and reflected the front and back legs over his back. Then I opened the abdomen and chest and reflected the ribs and muscles over his back with the legs.

Now I had both the chest and abdomen fully exposed. I noticed a few white streaks in the muscles of the hind legs. White muscle disease was immediately on the list of possibilities. Still, a few diseased fibers in the hind leg muscles would not lead to sudden death.

“Ryan, do you give your calves a Bo-Se injection when they are born?” I asked.

“No, I guess I don’t know what that is,” Ryan said.

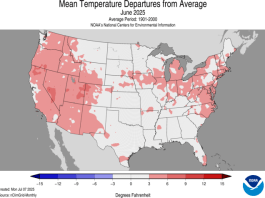

“It is a vitamin E and selenium supplement,” I said. “Western Oregon is in a significant selenium deficient area, and we need to supplement cows and their calves. Some mineral mixes have some selenium in them but not at a level that we need around here. I am working on a prescription mix with a guy up at Rufus, but it will probably be next year before that is available.”

“Do you think that is the problem?” Ryan said.

“I notice a few white streaks in the muscles of the hind legs,” I said. “That is not enough to cause sudden death. But white muscle disease has a cardiac form, and that often leads to sudden death. So I am going to look at this heart right now.”

I carefully opened the pericardium, the sac-like structure that contains the heart. Then I whacked through the great vessels and pulled the heart out where I could get a good look at it.

This was definitely a cardiac form of white muscle disease. The heart muscle was uniformly pale, and there were multiple white streaks in the muscles on the outside of the heart.

“Let’s take this over to the truck, and I will open it on the tailgate,” I said. “That way, I can show you what we have going on.”

I placed several layers of paper towels on the open tailgate to serve as a work surface. And then, with my large surgical scissors, I opened both sides of the heart.

I placed several layers of paper towels on the open tailgate to serve as a work surface. And then, with my large surgical scissors, I opened both sides of the heart.

“Ryan, the first thing we see when we look at this heart is the muscles are pale,” I explained as I pointed things out to Ryan. “Just compare this to the heart muscle you see in a slaughtered steer.”

“Yes, I see,” Ryan said. “This heart is really pale, and what are those white streaks I see on the surface?”

“Those are diseased muscle fibers,” I said. “Just like the streaks I could see in the hind leg muscles. The problem is, this is the heart, and diseased muscle fibers become more important than a sore leg.”

“I guess I’m getting the picture,” Ryan said.

“Look at the inside of this heart,” I said. “See all these white plaques on the lining of the left ventricle. This is definitely the cardiac form of white muscle disease. I can send some of these tissues in to confirm the diagnosis. Still, you need to get an injection of Bo-Se into these calves you have out in the pasture. Give an injection to any new calves as soon as they are born.”

“This will kill a calf overnight?” Ryan asked. “I mean, these two calves were normal last night.”

“Yes, sudden death is common with the cardiac form,” I said. “Sort of like a heart attack.”

“Well, if it’s that way in cattle, what about you and me?” Ryan asked.

“That is an interesting question,” I said. “I don’t think the medical profession fully addresses that question. They would rather blame red meat. But if you look at the incidence of heart attacks in men from Denver and compare that to men in Portland, or Sweet Home, you will probably see a difference. Denver has plenty of selenium; Sweet Home is deficient.”

“Maybe I should check my vitamin pills,” Ryan said.

“Yes, that probably helps,” I said. “And our diet is not restricted to local foods these days.

“Can I pick up that Bo-Se at your office?” Ryan asked.

“Can I pick up that Bo-Se at your office?” Ryan asked.

“Yes, and it’s important that you get that done today,” I said. “Give some MuSe to the cows is a good idea also, but that is not critical to do right away. I will put you on the list of ranches when I have the new mineral mix put together.”

“What is the difference between Bo-Se and Mu-Se?” Ryan asked.

“Just the concentration,” I said. “Bo-Se is one cc per forty pounds, and Mu-Se is one cc per two hundred pounds. You could probably get away with using Mu-Se on these calves. They are big enough and probably deficient enough that giving them one cc of Mu-Se would probably be okay and would be a little cheaper.”

“What do I need to do with these calves?” Ryan asked.

“You can just dispose of them however you do that,” I said. “There is no need to do anything special with them. There is nothing contagious here.”

“I have always heard of guys talk about white muscle disease,” Ryan said. “But I haven’t heard anyone say anything about finding dead calves.”

“Sometimes, that’s because this form doesn’t occur too often,” I said. “But the other side of that story is if you don’t look for something, you won’t find it.”

“You mean if I just assumed these calves died of whatever and drug them out to the brush for the coyotes, I would never have known I had a white muscle disease problem?” Ryan said.

“Exactly,” I said. “You always need to investigate a death. Maybe not so much in a sixteen-year-old cow, but any unexpected death, you find the cause.”

I lost a really nice QH filly to White Muscle disease when I lived in northern Wisconsin about 20 years ago. Had to learn the hard way that northern Wisconsin was deficient in selenium. After that the vet prescribed a selenium supplement to put on the pregnant mares grain.

Comments are closed.