Did your small grain forages get away from you during the fall? It’s been a common problem this winter. Snow mold from overgrown winter annual forage is certainly a risk, but we still don’t recommend cutting or grazing in the middle of winter.

You probably did your best with the information at hand. Much of that information was based off of the past few winters, when the cold slammed us hard and early. So the conventional wisdom was to play it safe. That meant planting on the early side to have enough growth to survive the winter, to get some fall tillering (at least two tillers per plant is recommended) and a good six inches of growth before winter set in. Temperatures reaching seventy on Christmas day were not in the plan.

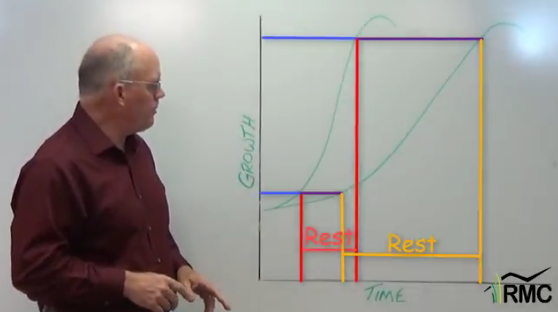

Weather that stays this balmy into the true beginnings of winter confuses the plant. As temperatures dip and stay in the 30s and 40s during the typical northeastern winter, small grains and other winter annuals take the signal to pause growth and begin dormancy. Without that signal, the plants are in danger of producing too much leafy top growth that is not hardened off and more susceptible to frost damage. Freeze damage that comes too suddenly before the plant goes dormant causes even more damage.

The excessive growth – especially stands of small grain forages when annual ryegrass is mixed in – is prone to lodging in wet conditions with snow fall. This can lead to snow mold, a fungus that thrives in the humid, dark, and airless conditions beneath the lodged forage. If it’s in a lower or poorly drained part of the field, the moisture in the area can also freeze over and cause more damage to the stand. And even if you don’t see ice sheeting on the plants, more moisture in bottomland soil means more freezing and damage around the root zone.

The risk of damage if you cut or graze, however, is greater.

Wheel or hoof traffic over heavily frosted forage will almost certainly cause higher losses than waiting out the winter. When the plants’ cells become frosted, they expand and are more vulnerable to rupturing beyond repair with disturbances like traffic. The ground may also be too wet, which causes compaction. When the root zone is compacted, the roots cannot get enough oxygen and may rot (at the very least, root growth is constrained), causing damage to the whole plant. Additionally, if the grazing down to 3-4 inches is followed quickly by a cold snap, the plant will go dormant and that amount of remaining stubble is not equipped to weather the harsh turn to winter. More top growth gives the plant greater root energy reserves to draw upon during cold spells when photosynthesis is stalled. It also provides more insulation to the plant’s crown. It’s recommended to be no more than six inches tall going into winter, however, or the growth is actually more susceptible to damage.

With the sudden drop off in temperatures we’ve seen this winter, small grain stands used to the warmth (especially those lacking snow cover) will suffer.

However, you can best reduce your losses by waiting until spring when the ground is dry enough to bring in the equipment or animals. At this point, losses will depend largely on the amount of snow cover your stand sees for the remainder of the winter.

It’s not until plants truly break dormancy at spring green-up time that you can begin to evaluate the success of your stand and see if a Plan B (such as oats or spring barley) is necessary.