Wildfires on the Great Plains are three times more frequent and four times bigger than they were thirty years ago. Some of the biggest increases in both size and frequency have occurred in the southern Great Plains. That’s an immense problem for both people and wildlife. In this 5 minute video from the Lesser Prairie Chicken Initiative (a partnership led by the Natural Resources Conservation Service), researchers, and Kansas rancher Ed Koger describe how patch burning and grazing combine to prevent wildfires and provide better grazing and habitat.

How Does Patch-Burn Grazing Work?

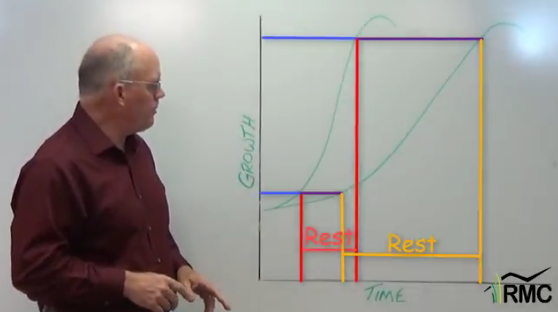

Patch-burn grazing, also sometimes called “pyric herbivory,” is an effort to mimic two processes that have shaped the prairie habitat for thousands of years: fire and grazing. Ignited by lightning and by native tribes, fire killed brush and trees and promoted resprouting of grasses, forbs and legumes. This regrowth was grazed down by large herbivores attracted to the high protein forage. Burning and grazing combined to create a grassland mosaic of different age patches, providing just the right habitat for a variety of wildlife, and just the right food for grazers.

This process is also a great way to prevent wildfires. Researchers have found that prescribed fire alone doesn’t reduce fire danger, since the plant biomass quickly rebuilds in the absence of grazing. On its own, prescribed fire would need to be performed annually to keep the fuel load down. That fire frequency would reduce biodiversity, creating a uniform grassland landscape that lacks the kind of structural and species diversity that are important for the lesser prairie-chickens and other prairie wildlife, and would severely impact rancher’s ability to make a living.

For Ed Koger, the reasons for patch burning are clear, “As long as I incorporate fire in my management of the prairie on this ranch,” he says, “I’m going to have more wildlife, and I’m going to produce more pounds of beef. Back in the 70s, I had a few prairie-chickens—20 to 30 birds, maybe. When I started cutting the cedars aggressively and started burning, the numbers started going up. The more I cut and burned, the more chickens there were, along with quail, and grasshopper sparrows, and everything else.”

How Can I Get Started?

As both Ed Koger and Bill Barby note in the video, you need the right support to successfully use prescribed fire. One way to get started is to check in with your local NRCS office to see what kind of assistance is available in your area. We’ll also be sharing more information in future issues.

The Lesser Prairie-Chicken Initiative (LPCI), a partnership led by USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS), focuses on working with ranchers on implementing practices that are good for the herd and the bird. If you’re working in an area identified as lesser prairie -chicken habitat, contact your local NRCS office to learn more about how they can help you implement practices that improve forage, habitat, and your bottom line.

The Lesser Prairie-Chicken Initiative (LPCI), a partnership led by USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS), focuses on working with ranchers on implementing practices that are good for the herd and the bird. If you’re working in an area identified as lesser prairie -chicken habitat, contact your local NRCS office to learn more about how they can help you implement practices that improve forage, habitat, and your bottom line.

Thanks to Sandra Murphy for contributions to this article!

Great article. DWK- my pastures are covered in plains prickly pear cactus and fringed sage. I didn’t think fire removed cactus. More info would be nice. Thanks

Paul, here’s how another reader uses cactus as a Forage on his place: Use cactus to cut your winter feed bill in half.

Good article, I have been doing this when I burn cactus.

You would think places like California would do something similar to this around subdivisions to build buffers from wild fires.

Comments are closed.