Before I began farming, I was an oceanographer. I used to study tiny, planktonic crustaceans called copepods that feed on microscopic algae, at the base of the food chain, and are themselves consumed by fishes. Some 70 percent of all fishes in the ocean eat copepods at some time in their lives. So naturally, oceanographers and marine biologists are interested in identifying the factors that drive copepod production. My particular interest was in how the kinds of algae that copepods eat affect their egg production – an indication of their health.

Before I began farming, I was an oceanographer. I used to study tiny, planktonic crustaceans called copepods that feed on microscopic algae, at the base of the food chain, and are themselves consumed by fishes. Some 70 percent of all fishes in the ocean eat copepods at some time in their lives. So naturally, oceanographers and marine biologists are interested in identifying the factors that drive copepod production. My particular interest was in how the kinds of algae that copepods eat affect their egg production – an indication of their health.

In 1991, I conducted an experiment to document that relationship. I collected some copepods with a net and transferred a few females and a male to each of several jars containing filtered sea water. To one set of jars, I added a single species of alga, belonging to a group known as the diatoms. To another set of jars, I added a different algal species belonging to a group called the dinoflagellates. And to a third set of jars, I added a mixture of diatoms and dinoflagellates. The total amount of food was the same in all three groups of jars.

The copepods in jars containing only diatoms produced about 10 eggs per female each day. The copepods in the dinoflagellate jars, produced about 70 eggs per female each day. That was no surprise, since dinoflagellates are known to contain more protein and lipids (energy) than diatoms.

But what came next was surprising. One would expect that by mixing the less and more nutritious algae together, the copepod’s egg production would be somewhere between that observed with each alga alone. Instead, egg production soared to well over 100 eggs per female per day! The more diverse diet supported a significantly higher egg-production than did either food alone.

What Does This Have to Do With Grazing?

It turns out diversity in pasture improves animal performance too!

Fast forward to 2012. Now I am a farmer. I’m also an agricultural ecologist, studying the use of sheep to manage the spread of invasive plants in grasslands. One of my students, Corine Giroux, is managing a flock in rough terrain near Albany, NY. The landscape is too rugged to brush hog very often so it’s overgrown with a variety of grasses, forbs and brush. As her undergraduate honors thesis, Corine has decided to compare the body condition scores of the sheep she is managing in this wild landscape to the flock at my farm, where the animals feed on a well-managed pasture dominated by Timothy, orchard grass and red-clover. She’s hoping to determine the extent to which the poor-quality pasture that her sheep are grazing limits their body condition score relative to the animals in my carefully managed pasture.

Remember that body condition scoring is performed by feeling the sheep’s spine and pelvis, and ranking the layering of meat-and-fat-over-bone on a scale from 1 to 5. If the animal’s bones are really noticeable, like the knuckles on your fist, the sheep is considered emaciated. It receives a score of 1. If you detect little bone structure, like the back of your hand, the sheep is obese. It receives a body condition score of 5. If the spine feels like the fingers as you run your hand across your clenched fist, the animal receives an optimal body condition score of 3. So three is where you want to be.

Corine compared the body condition scores of my sheep with those that she was managing on the wild site by calculating how much the average of the herd’s body scores deviated from the optimal value of 3. The lower the deviation the better. What she found surprised both of us. While most of the sheep in both flocks had body condition scores close to the optimal value, sheep on the wilder, weedier landscape had a lower average deviation from the optimal score than those on the well-tended pasture. In other words, sheep eating the more wild diet were healthier.

In an effort to explain her results, Corine counted the number of plant species in both pastures. Then, by analyzing the plant remains in sheep feces from each pasture, she determined the percentages of different kinds of plants in the diet. Long story, short, the diversity of plants both in the pasture and in the diet, was higher in the wilder landscape than in the well managed pasture. Like the copepods in my study some 30 years earlier, diversity was linked to animal health.

What Can You Do With This?

Corine’s results led me to change the way I manage my pastures. For one thing, I stopped mowing. And when I did, the number of species of plants in my pasture shot up. I’ve also noticed more pollinators in the pasture, especially in the fall, when the bees get their last nectar of the season from the golden rod. The deviation around the optimal body condition score in my flock has dropped in half. As an added benefit, I’m putting less time and money into tractor maintenance than when I was mowing the pasture. I’m also using 70 percent less diesel than when I was mowing, and I’m putting about a ton less carbon into the atmosphere each year.

Gary is the author of “The Emergent Agriculture: Farming, Sustainability and the Return of the Local Economy.” It documents the revolutionary changes underway in food production, marketing and consumption – rejecting industrial production for a smaller, healthier more ethical food system. It tells the stories of some of the farmers, scientists and economists who are making it all happen. You can get The Emergent Agriculture from the author at www.thefarmatlongfield.com or at www.amazon.com.

Gary is the author of “The Emergent Agriculture: Farming, Sustainability and the Return of the Local Economy.” It documents the revolutionary changes underway in food production, marketing and consumption – rejecting industrial production for a smaller, healthier more ethical food system. It tells the stories of some of the farmers, scientists and economists who are making it all happen. You can get The Emergent Agriculture from the author at www.thefarmatlongfield.com or at www.amazon.com.

Gary, thank you for sharing! As I plan to try not mowing this season for the very same reason I am curious it you use temporary electric netting and if you have found the non-mowing to inhibit the strength of your fences?

Yes, we do use temporary electric fencing and there can be a loss of charge, especially when the pasture is wet. I use a weed whacker or a small mower to cut a fence line early in the season and I try to return to the same line on each subsequent rotation (though that’s not always possible).

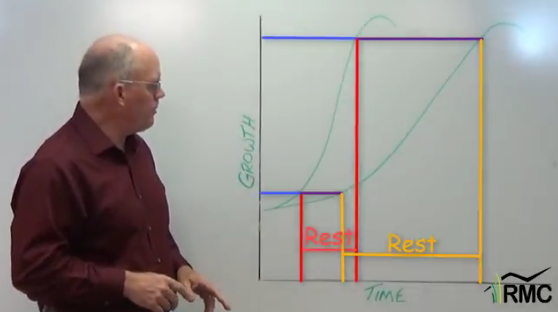

Many variables impact health and body condition score but . . . . I’ve witnessed similar results with cattle and goats as well. The chance to pick and choose is great for them but to maximize gain per acre ranchers also need to limit access to mimic the predator driven herd behavior before european settlement. Movement and long rest balanced with a diverse diet. Good article and I look forward to the follow-up.

Thanks for your comment Jesse. Fred Provenza did some really interesting research on dietary diversity. He also edited a book with Michele Meuret called, The Art & Science of Shepherding that documents the amazing French high country shepherds who move their flocks through vegetatively diverse landscapes which provides in balance in the diet and excellent growth in the livestock. A good read.

Need more detail. How did the sheep in managed pasture deviate? Emaciated or obese?

Thanks for your question Gary. To answer, let me say that both flocks had good body condition scores (BSCs). The way Corine calculated deviation is that she subtracted each BCS that she measured on her sheep and she did the same with the data that I measured on my sheep. She looked at the “absolute value” of each deviation, so that deviations were positive. Then she took the mean of the deviations. So this method doesn’t really look at whether the sheep were closer to 1 or 5, just where there was more variability.

You probably noticed that my response to your question was not clear. The sentence “The way Corine calculated deviation is that she subtracted each BCS that she measured on her sheep…”, should read:

“The way Corine calculated deviation is that she subtracted each BCS that she measured on her sheep from the optimal value of 3… ”

Hope that makes it clearer.

The meaning was clear enough even if the language was off a bit. Still, the needed data is the measured BCS. That’s the science part. Data.

Another resource for value of grazing plant diversity is Fred Provenza’s research at Utah State. Contact Beth Burritt for help in getting this research.

Here’s the website for information about research done by Fred Provenza and his colleagues: http://behave.net

Beth Burritt manages the site and has done a great job of providing information and a list of all the research. Thanks, Beth! And thanks, Chip, for pointing this out!

I had another paragraph in this article that described some of Fred’s work, but we decided to save it for another article. Stay tuned.

Comments are closed.