“If you can’t stand the heat, get out of the kitchen.” But what if you’re a plant and that’s just not possible? It turns out they have other options. Researchers from Japan have discovered that plants can gain heat tolerance to better adapt to future heat stress, thanks to a particular mechanism for heat stress ‘memory’.

“If you can’t stand the heat, get out of the kitchen.” But what if you’re a plant and that’s just not possible? It turns out they have other options. Researchers from Japan have discovered that plants can gain heat tolerance to better adapt to future heat stress, thanks to a particular mechanism for heat stress ‘memory’.

In a study published in Nature Communications, researchers from Nara Institute of Science and Technology have revealed that a family of proteins that control small heat shock genes enables plants to ‘remember’ how to deal with heat stress.

Climate change, especially global warming, is a growing threat to agriculture worldwide. Because plants can’t move to avoid adverse conditions, such as potentially lethal high temperatures, they need to be able to deal with factors such as heat stress effectively to survive. Therefore, improving the heat tolerance of crop plants is an important goal in agriculture.

“Heat stress is often repeating and changing,” says lead author of the study Nobutoshi Yamaguchi. “Once plants have undergone mild heat stress, they become tolerant and can adapt to further heat stress. This is referred to as heat stress ‘memory’ and has been reported to be correlated to epigenetic modifications.” Epigenetic modifications are inheritable changes in the way genes are expressed, and do not involve changes in the underlying DNA sequences.

“We wanted to discover how plants retain a memory of environmental changes,” explains Toshiro Ito, senior author. “We examined the role of JUMONJI (JMJ) proteins in acquired temperature tolerance in response to recurring heat within a few days.”

Now, this is where what they learned gets complicated for anyone without a solid understanding of chemistry, gene structure, epigenetics and how it all works together.

Here’s their scientific explanation of what’s happening:

JUMONJI proteins are histone demethylases. Demethylases are enzymes that remove methyl groups from molecules such as proteins, particularly histones, which provide structural support to chromosomes. The team revealed that plants are able to maintain heat memory because of lowered H3K27me3 (histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation) on small heat shock genes.

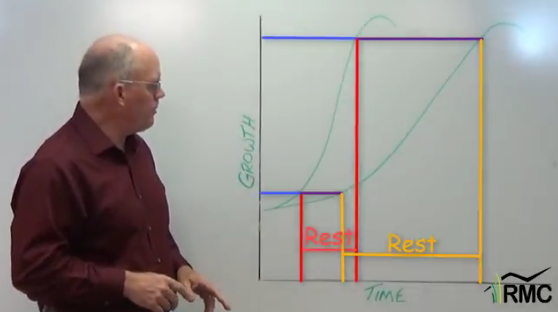

Now, here’s a picture of what’s going that the rest of us can grasp:

On the left you see a plant that has been heat stressed but hasn’t yet acclimated. See the little round circles attached to each heat shock protein? Those are the methyl groups. On the right you can see that the little PacMan-like JUMONJI protein as “eaten” two of those proteins, and in the process has created a “memory” path for the plant to acclimate and deal with future heat stress.

And why do we care?

Mr. Yamaguchi says, “We found that these proteins are necessary for heat acclimation in Arabidopsis thaliana (the plant they used for their studies). These results, along with future studies, will further clarify the mechanisms of plant memory and adaptation.” He says this research will be relevant to genetic research in a number of fields, including biology, biochemistry, ecology, and environmental and agricultural sciences, and is applicable to the study of animals as well as plants.

For the rest of us, it means that, by understanding these mechanisms, we have opportunities to help plants develop memories that will improve their heat tolerance to maintain the food supply in natural conditions.

If you’d like to read the full paper, you can find it here: H3K27me3 demethylases alter HSP22 and HSP17.6C expression in response to recurring heat in Arabidopsis

You can learn more about Project leader Ito’s lab can and the work he is doing here.

Thanks, Kathy for sharing how this works, at the molecular level. Could stress-induced epigenetics also lower my winter feed costs? And increase herd longevity?

You’ve posted several times over the years, ongoing work of Andy Roberts, USDA-ARS. On the surprising benefits of winter-restricted feed while developing heifers. This ‘stress’ appears to result in generations of more efficient feeding cattle. With potential to move the whole herd to that goal. Helping to reduce winter feed costs. With statistically same breeding rates and higher rates of longevity, if I’m reading the research correctly. Though thinner heifers need to be gaining weight to breed well and keep calves.

https://onpasture.com/2020/06/29/another-benefit-of-smaller-cows-they-make-fatter-calves/

(and the paper you link there)

Apparently there are epigenetic changes occurring in the mother, the fetus she’s carrying during feed reduction, and her developing fetal eggs. Three generations in one animal, each being shaped to thrive more on forages. Strains my brain to grasp that…

So epigenetics can help me reduce winter feed costs? And build a herd that thrives on more pasture, less inputs? That’s practical, whether we’ve yet to work out the details!

I love to see you making these connections! And yes, you’re right. This seems to be what the research and studies of epigenetics are telling us. In fact, I’ve read studies with similar results in humans. Mothers who went through the Dutch Famine of WWII had children who were prone to obesity. (https://www.cuimc.columbia.edu/news/study-shows-how-effects-starvation-can-be-passed-future-generations). And children of adults who lived through the famine in China in the mid-20th century were more prone to hyperglycemia. (https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/12/161212115737.htm). It’s all very interesting! 🙂

Comments are closed.