“Adaptive, multipaddock rotational grazing management did not enhance vegetation productivity or the density of perennial C3 [cool season] grasses, but it did markedly reduce livestock performance.”

“Rotational grazing as a means to increase vegetation and animal production has been subjected to as rigorous a testing regime as any hypothesis in the rangeland profession, and it has been found to convey few, if any, consistent benefits over continuous grazing. It is unlikely that researcher oversight or bias has contributed to this conclusion given the large number of grazing experiments, investigators, and geographic locations involved over a span of six decades.

“The experimental evidence indicates that rotational grazing is a viable grazing strategy on rangelands, but the perception that it is superior to continuous grazing is not supported by the vast majority of experimental investigations. There is no consistent or overwhelming evidence demonstrating that rotational grazing simulates ecological processes to enhance plant and animal production compared to that of continuous grazing on rangelands.”

Now, if you’re feeling some defensiveness, or some irritation or even anger, you’re not alone. There were plenty of people that felt just that when they read it thirteen years ago. So, it started the kind of discussion scientists often have where they ask questions like: What are the potential weaknesses in past research? What new research would address those weaknesses to see if the results are different? Then they got to work.

Because all that takes time, the discussion has carried on for over a decade, with this 2020 paper the latest contribution to our understanding. The study responds to suggestions that past research wasn’t adequate because it was not done on a landscape scale, studies were short-term, and they did not test for the benefits of good adaptive management.

The study took place at the Central Plains Experimental Range, a Long-Term Agroecosystem Research site established in 1939. Twenty 130-hectare pastures (321 acres) were paired into 10 blocks, each containing two similar pastures. One pasture in each pair was randomly assigned to either the Traditional Rangeland Management treatment (TRM) of season-long, continuous grazing, or to the Collaborative Adaptive Rangeland Management treatment (CARM). The CARM pastures were managed adaptively by an 11-member stakeholder group working to reach vegetation, livestock, and wildlife goals. Because this was a research project the group had the benefit of information about precipitation, forecasts, vegetation quality and quantity on which to make their decisions. The paper carefully outlines all the decisions made and their attention to ensuring that both treatments were managed and measured equally and fairly. We’ll talk more about that in future issues.

1) Year-long rest periods in the adaptively managed, rotational pastures would increase the density and productivity of perennial C3 graminoids [cool season grasses] compared with continuously grazed pastures. (These cool season grasses are key to grazing success on semi-arid rangelands and increasing their abundance is a common goal.)

2) Adaptive management, supported with detailed monitoring data, would result in similar cattle performance in the rotational as in the continuously grazed pastures.

What they found was that there was no difference in cool-season grass abundance between the two treatments. In addition, adaptive, rotational grazing resulted in a 12-16% reduction in total cattle weight gain each year.

When I talked to one of the authors of this paper, he said that the results were surprising to him, and kind of hard to take. As part of the stakeholder group, he knew how hard they had all worked to create a good outcome, and everyone felt like they’d done an excellent job. It was not for lack of trying that they arrived at this result.

This perception of what increased attention to management and rotation should provide is one of the issues the 2008 paper pointed out, and the authors explored why it is that our perceptions don’t match our outcomes. That’s something we’ll talk about in future issues, including a look at the history of how we developed some of our expectations. We’ll also look at recommended stocking rates and how they factor into all of this.

Finally, before you write me an impassioned and perhaps angry comment or email, please know that I’m simply offering information I think is helpful to everyone’s success. Also, remember that these papers are specific to semi-arid regions and may not address your specific location. If there is an article you’d like to add to the mix, please send it on and I will gladly read it and include thoughts in future issues. Likewise, I hope you’ll read the two papers this article is discussing as I think you’ll find them very thoughtful and interesting. If you don’t have time right now, know that we’ll be looking at them in greater depth.

I am the founder, editor and publisher of On Pasture, now retired. My career spanned 40 years of finding creative solutions to problems, and sharing ideas with people that encouraged them to work together and try new things. From figuring out how to teach livestock to eat weeds, to teaching range management to high schoolers, outdoor ed graduation camping trips with fifty 6th graders at a time, building firebreaks with a 130-goat herd, developing the signs and interpretation for the Storm King Fourteen Memorial trail, receiving the Conservation Service Award for my work building the 150-mile mountain bike trail from Grand Junction, Colorado to Moab, Utah...well, the list is long so I'll stop with, I've had a great time and I'm very grateful.

This is my first time reading “On Pasture”, but this analysis has me hooked! Thanks Kathy, appreciate how active you are in the comments, explaining your thoughts and backing it up with your experience and research. Many thanks from this young, hopeful future grazier! Can’t wait to read some more!

As someone who has been reading, teaching and experimenting about grazing since 1988, I was surprised. Recently I developed and taught a course on Sustainable Practices in Agriculture and am preparing to teach it again soon. I also wonder about changes in soil carbon content in these experiments and whether the rotational grazing involved grazing down to bare earth or leaving half the standing height of forage for regeneration.

Hi Paul,

I think that when you read the paper, you’ll see that their rotational grazing did not include grazing down to bare earth. You might also be interested in the study “Collaborative Adaptive Rangeland Management, Multipaddock Rotational Grazing, and the Story of the Regrazed Grass Plant” in Rangeland and Ecology Management from September of 2021 which found similar results. And with just a bit of exploration, I’ve been finding more articles like this today. It seems like something I should gather and present to On Pasture readers.

Regarding soil carbon content, scientists in this same LTAR have studied soil carbon content and grazing’s contribution to increases or decreases for a very long time. I covered some of that research here. They and others don’t arrive at the answers we most hope for – that grazing in a particular fashion makes a big difference. And again, I have collected more papers like that just today.

You might also find the 2008 paper by Briske et al interesting where they talk about the history of the concept of rotational grazing and the role that perception plays in our decisions. I found it very interesting.

Again, none of this is to say that rotational grazing is not a viable management tool. It simply points out some interesting things that we may not have been aware of and that may be helpful to graziers.

With the test hypothesis of this study is C3 grass improvement and animal performance, I am sure their data is accurate. My concern with any of the studies that have been conducted on grazing management is they all seem to maintain a narrow focus while the landscapes are not 2 dimensional.

It would be interesting to have them examine any soil health variations between the sites, plant diversity changes and variations in wildlife populations.

Hi Paul,

I highly recommend downloading and reading the paper as it will give you information on plant diversity changes and variations in wildlife populations. They’ve done other work on soil health in the same LTAR and they have long term info since they started work there in 1939. I might be able to find something for you as well.

The devil is in the details. The average number of grazing days for each of the CARM pastures during the 5-year study was about 3 weeks. That is too long of a grazing period in my opinion to truly see benefits in that short of a time frame. When I asked one of the authors why they didn’t double the number of pastures to 20 (to shorten the grazing periods and increase the stock density) and do a longer-term study, he said it was a financial decision. I question that. Temporary electric fence really doesn’t cost that much.

Hi Dan,

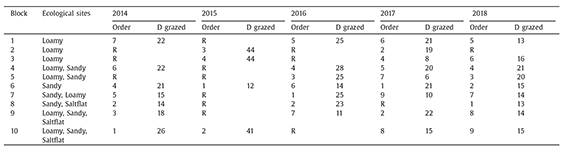

I thought this was an interesting point, so I went to look at the number of days grazed and the order in which pastures were grazed over the 5 year period of the study. What I was interested in was whether the same pasture was grazed at the same time every year, and it seems they did a really good job of rotating timing to provide rest to cool season grasses so they could potentially increase. I thought that maybe they were looking at it that way. I’ve attached the graph here, but you can see it better if you download the paper.

Perhaps Alderspring Ranch could comment on their experience in a drought year on open range.

Can you point us to what the science says about areas that are not semi-arid? Say 40 inches of rainfall or so per year? Thx.

This is my first time reading “On Pasture”, but this analysis has me hooked! Thanks Kathy, appreciate how active you are in the comments, explaining your thoughts and backing it up with your experience and research. Many thanks from this young, hopeful future grazier! Can’t wait to read some more!

As someone who has been reading, teaching and experimenting about grazing since 1988, I was surprised. Recently I developed and taught a course on Sustainable Practices in Agriculture and am preparing to teach it again soon. I also wonder about changes in soil carbon content in these experiments and whether the rotational grazing involved grazing down to bare earth or leaving half the standing height of forage for regeneration.

Hi Paul,

I think that when you read the paper, you’ll see that their rotational grazing did not include grazing down to bare earth. You might also be interested in the study “Collaborative Adaptive Rangeland Management, Multipaddock Rotational Grazing, and the Story of the Regrazed Grass Plant” in Rangeland and Ecology Management from September of 2021 which found similar results. And with just a bit of exploration, I’ve been finding more articles like this today. It seems like something I should gather and present to On Pasture readers.

Regarding soil carbon content, scientists in this same LTAR have studied soil carbon content and grazing’s contribution to increases or decreases for a very long time. I covered some of that research here. They and others don’t arrive at the answers we most hope for – that grazing in a particular fashion makes a big difference. And again, I have collected more papers like that just today.

You might also find the 2008 paper by Briske et al interesting where they talk about the history of the concept of rotational grazing and the role that perception plays in our decisions. I found it very interesting.

Again, none of this is to say that rotational grazing is not a viable management tool. It simply points out some interesting things that we may not have been aware of and that may be helpful to graziers.

With the test hypothesis of this study is C3 grass improvement and animal performance, I am sure their data is accurate. My concern with any of the studies that have been conducted on grazing management is they all seem to maintain a narrow focus while the landscapes are not 2 dimensional.

It would be interesting to have them examine any soil health variations between the sites, plant diversity changes and variations in wildlife populations.

Hi Paul,

I highly recommend downloading and reading the paper as it will give you information on plant diversity changes and variations in wildlife populations. They’ve done other work on soil health in the same LTAR and they have long term info since they started work there in 1939. I might be able to find something for you as well.

The devil is in the details. The average number of grazing days for each of the CARM pastures during the 5-year study was about 3 weeks. That is too long of a grazing period in my opinion to truly see benefits in that short of a time frame. When I asked one of the authors why they didn’t double the number of pastures to 20 (to shorten the grazing periods and increase the stock density) and do a longer-term study, he said it was a financial decision. I question that. Temporary electric fence really doesn’t cost that much.

Hi Dan,

I thought this was an interesting point, so I went to look at the number of days grazed and the order in which pastures were grazed over the 5 year period of the study. What I was interested in was whether the same pasture was grazed at the same time every year, and it seems they did a really good job of rotating timing to provide rest to cool season grasses so they could potentially increase. I thought that maybe they were looking at it that way. I’ve attached the graph here, but you can see it better if you download the paper.

Perhaps Alderspring Ranch could comment on their experience in a drought year on open range.

Can you point us to what the science says about areas that are not semi-arid? Say 40 inches of rainfall or so per year? Thx.